Ashanti Empire

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ashanti Empire or Asante Empire, also known as the Ashanti Confederacy or Asanteman (independent from 1701–1896), was a pre-colonial West African state created by the Akan people of what is now the Ashanti Region in Ghana. Their empire stretched from central Ghana to present day Togo and Côte d'Ivoire, bordered by the Dagomba kingdom to the north and Dahomey to the east. Today, the Ashanti monarchy continues as one of the constitutionally protected, sub-national traditional states within the Republic of Ghana.

Origins

The Ashanti or Asante are a major ethnic group in Ghana. They were a powerful, militaristic, and highly disciplined people of West Africa. The ancient Ashanti migrated from the vicinity of the northwestern Niger River after the fall of the Ghana Empire in the 13th century. Evidence of this lies in the royal courts of the Akan kings reflected by that of the Ashanti kings whose processions and ceremonies show remnants of ancient Ghana ceremonies. Ethno linguists have substantiated the migration by tracing word usage and speech patterns along West Africa.

Around the 13th century AD, the Ashanti and various other Akan peoples migrated into the forest belt of present-day Ghana and established small states in the hilly country around present-day Kumasi. During the height of the Mali Empire the Ashanti, and Akan people in general, became wealthy through the trading of gold mined from their territory. Early in Ashanti history, this gold was traded with the greater Ghana and Mali Empires. Dubious; cite [Academic citations on the Talk page directly contradict this uncited account]

Kingdom Formation

Akan political organization centered on various clans, each headed by a paramount chief or Amanhene.[3] One of these clans, the Oyoko, settled Ghana’s sub-tropical forest region, establishing a center at Kumasi.[4] During the rise of another Akan state known as Denkyira, the Ashanti became tributaries. Later in the mid-17th century, the Oyoko clan under Chief Oti Akenten started consolidating other Ashanti clans into a loose confederation that occurred without destroying the authority of each paramount chief over his clan.[5] This was done in part by military assault, but largely by uniting them against the Denkyira, who had previously dominated the region.

The Golden Stool

Another tool of centralization under Osei Tutu was the introduction of the 'Golden Stool' (sika 'dwa). According to legend, a meeting of all the clan heads of each of the Ashanti settlements was called just prior to independence from Denkyira. In this meeting, the Golden Stool was commanded down from the heavens by Okomfo Anokye, the Priest or sage advisor, to Asantehene Osei Tutu I. The Golden stool floated down, from the heavens straight into the lap of Osei Tutu I. Okomfo Anokye declared the stool to be the symbol of the new Asante Union ('Asanteman'), and allegiance was sworn to the Golden Stool and to Osei Tutu as the Asantehene. The newly founded Ashanti union went to war with Denkyira and defeated it.[6] The Golden Stool remains sacred to the Ashanti as it is believed to contain the 'Sunsum' (pronounced 'soon-soom')— spirit or soul of the Ashanti people.

Independence

In the 1670s, then head of the Oyoko clan, Osei Kofi Tutu I, began another rapid consolidation of Akan peoples via diplomacy and warfare.[7] King Osei Kofu Tutu I and his chief advisor, Okomfo Kwame Frimpon Anokye led a coalition of influential Ashanti city-states against their mutual oppressor, the Denkyira who held Asanteman as one of its tributaries. Asanteman utterly defeated them at the Battle of Feyiase, proclaiming its independence in 1701. Subsequently, through hard line force of arms and savoir-faire diplomacy, the duo induced the leaders of the other Ashanti city-states to declare allegiance and adherence to Kumasi, the Ashanti capital. Right from the onset, King Osei Tutu and Priest Anokye followed an expansionist and an imperialistic provincial foreign policy.

Asanteman under Osei Tutu

Realizing the strengths of a loose confederation of Akan states, Osei Tutu strengthened centralization of the surrounding Akan groups and expanded the powers of the judiciary system within the centralized government. Thus, this loose confederation of small city-states grew into a kingdom or empire looking to expand its borders. Newly conquered areas had the option of joining the empire or becoming tributary states.[8] Opoku Ware I, Osei Tutu's successor, extended the borders, embracing much of present day Ghana's territory.[9]

Geography

The Ashanti Empire was one of a series of kingdoms along the coast including Dahomey, Benin, and Oyo. All of these states were based on trade, especially gold, ivory, and slaves, which were sold to first Portuguese and later Dutch and British traders. The region also had dense populations and large agricultural surpluses, allowing the creation of substantial urban centres. By 1874, the Ashanti controlled over 100,000 square kilometers while ruling approximately 3 million people.[2]

Economy

The lands within Asanteman were also rich in river-gold and kola nuts, and they were soon trading with the Songhai Empire, the Hausa states and with the Portuguese at the coastal fort Sao Jorge da Mina, later Elmina. Thanks largely to profits from the slave trade, the Ashanti had risen to be a major force in the area.[10]

Daily life

The history of the confederacy was one of slow centralization. In the early 19th century the Asantehene used the annual tribute to set up a permanent standing army armed with rifles, which allowed much closer control of the confederacy. Despite still being called a confederacy it was one of the most centralised states in sub-Saharan Africa. Osei Tutu and his successors oversaw a policy of political and cultural unification and the union had reached its full extent by 1750. It remained an alliance of several large towns which acknowledged the sovereignty of the ruler of Kumasi, known as the Asantehene.

Agriculture

The Ashanti prepared the fields by burning before the onset of the rainy season and cultivated with an iron hoe. Fields are fallowed for a couple years, usually after two to four years of cultivation. Plants cultivated include plantains, yams, manioc, corn, sweet potatoes, millet, beans, onions, peanuts, tomatoes, and many fruits. Manioc and corn are New World transplants introduced during the Atlantic European trade. Many of these vegetable crops could be harvested twice a year and the cassava (manioc), after a two-year growth, provides a starchy root. The Ashanti transformed palm wine, maize and millet into beer, a favorite drink; and made use of the oil from palm for many culinary and domestic uses.

Clothing

The main cloth of the Ashanti was the kente cloth, known locally as nwentoma. Clothing production was typically gender specialized. "The Covering of the State," is made of camel's hair and wool. An ornamental figurine, plated with gold or silver, topped all ceremonial umbrellas.

Family

Standing among families was largely political. The royal family typically tops the hierarchy, followed by the families of the chiefs of territorial divisions. In each chiefdom, a particular female line provides the chief. A committee from among several men eligible for the post elects that chief.

Children

Tolerant parents are typical among the Ashanti. Childhood is considered a happy time and children cannot be responsible for their actions. The child is not responsible for their actions until after puberty. A child is harmless and there is no worry for the control of its soul, the original purpose of all funeral rites, so the ritual funerals typically given to the deceased Ashanti are not as lavish for the children.

The Ashanti adored twins when they were born within the royal family because they were seen as a sign of impending fortune. Ordinarily, boy twins from outside of it became fly switchers at court and twin girl’s potential wives of the King. If the twins are a boy and girl, no particular career awaits them. Women who bear triplets are greatly honored because three is regarded as a lucky number. Special rituals ensue for the third, sixth, and ninth child. The fifth child (unlucky five) can expect misfortune. Families with many children are well respected and barren women scoffed.

Menstruation and impurity

The Ashanti held puberty rites only for females. Fathers instruct their sons without public observance. The privacy of boys was respected in the Ashanti kingdom. As menstruation approaches, a girl goes to her mother's house. When the girl's menstruation is disclosed, the mother announces the good news in the village beating an iron hoe with a stone. Old women come out and sing Bara (menstrual) songs. The mother spills a libation of palm wine on the earth and recites the following prayer:

“Supreme Sky God, who alone is great, Upon whom men lean and do not fall, Receive this wine and drink."

"Earth Goddess, whose day Of worship is Thursday, Receive this wine and drink, Spirit of our ancestors, Receive this wine and drink"

"O Spirit Mother do not come, And take her away, And do not permit her, To menstruate only to die.”

Menstruating women suffered numerous restrictions. The Ashanti viewed them as ritually unclean. They did not cook for men, nor did they eat any food cooked for a man. If a menstruating woman entered the ancestral stool house, she was arrested, and the punishment was typically death. If this punishment is not exacted, the Ashanti believe, the ghost of the ancestors would strangle the chief. Menstruating women lived in special houses during their periods as they were forbidden to cross the threshold men's houses. They swore no oaths and no oaths were sworn for or against them. They did not participate in any of the ceremonial observances and did not visit any sacred places.

Slavery in Asanteman

Slaves, the modern day Ashanti point out, were seldom abused.[11] A person who abuses a slave was held in high contempt by society. They further demonstrate the “humanity” of Ashanti slavery (in relation to slavery in the Americas) by pointing out those slaves were allowed to marry, and the children of slaves were born free. If found desirable a female slave may become a wife, the master preferred such a status to that of a free woman in a conventional marriage, because this type of marriage allowed the children to inherit some of the father's property and status.

This favored arrangement occurred primarily because of conflict with the matrilineal system. The Ashanti slave master felt more comfortable with a slave girl or pawn wife who had no abusua (older male grand father, father, uncle or brother) to intercede on her behalf every time the couple argued. With the wife's slave status, the man controlled his children unquestionably with the mother isolated from her own kin.

Slaves were often used for sacrifices in funeral ceremonies. The Ashanti believed that slaves would follow their masters into the afterlife.[12][13]

Death in Asanteman

Sickness and death are major events in the kingdom. The ordinary herbalist divines the supernatural cause of the illness and treats it with herbal medicines. The medicine man, a person possessed by a spirit, combats pure witchcraft.

If the patient fails to respond to medicine, the family performed the last rites. Then a member of the family poured water down the throat of the dying person when it is believed the soul is leaving the body and recite the following prayer:

Your abusua [naming them] say: Receive this water and drink, and do not permit any evil to come whence you are setting out, and permit all the women of the household to bear children.

People loathed being alone for long without someone available to perform this rite before the sick collapsed. The family washes the corpse, dresses it in its best clothes, and adorns it with packets of gold dust (money for the after-life), ornaments, and food for the journey "up the hill." The body was normally buried within 24 hours. Until that time the funeral party engage in dancing, drumming, shooting of guns, and much drunkenness, all accompanied by the wailing of relatives. This was done because the Ashanti typically believed that death was not something to be sad about, but rather a part of life. Of course, funeral rites for the death of a King involve the whole kingdom and are much more of an elaborate affair.

The greatest and most frequent ceremonies of the Ashanti recalled the spirits of departed rulers with an offering of food and drink, asking their favor for the common good, called the Adae. The day before the Adae, talking drums broadcast the approaching ceremonies. The stool treasurer gathers sheep and liquor that will be offered. The chief priest officiates the Adae in the stool house where the ancestors came. The priest offers each food and a beverage. The public ceremony occurs outdoors, where all the people joined the dancing. Minstrels chant ritual phrases; the talking drums extol the chief and the ancestors in traditional phrases.

The Odwera, the other large ceremony, occurs in September and typically lasted for a week or two. It is a time of cleansing of sin from society the defilement, and for the purification of shrines of ancestors and gods. After the sacrifice and feast of a black hen—of which both the living and the dead share, a new year begins in which all were clean, strong, and healthy.

Government

The Ashanti government was built upon a sophisticated bureaucracy in Kumasi, with separate Ministries to handle the state's affairs. Of particular note was Ashanti's Foreign Office based in Kumasi; despite its small size, the Ashanti Foreign Office allowed the state to pursue complex arrangements with foreign powers, and the Office itself contained separate departments for handling relations with the British, French, Dutch, and Arabs individually. Scholars of Ashanti history, such as Larry Yarak and Ivor Wilkes, disagree over the actual power of this sophisticated bureaucracy in comparison to the Asantahene, but agree that its very existence pointed to a highly developed government with a complex system of checks and balances.

Asantehene

At the top of Ashanti's power structure sat the Asantehene, the King of Ashanti. Each Asantahene was crowned on the sacred Golden Stool, the Sika 'dwa, an object which came to symbolise the very power of the King. Osei Kwadwo (1764–1777) began the system of appointing central officials according to their ability, rather than their birth.[14]

As King, the Asantehene held immense power in Ashanti, but did not enjoy absolute royal rule, and was obliged to share considerable legislative and executive powers with Asante's sophisticated bureaucracy. The Asantehene was the only person in Ashanti permitted to invoke the death sentence. During wartime, the King acted as Supreme Commander of the army, although during the 19th century, actual fighting was increasingly handled by the Ministry of War in Kumasi. Each member of the confederacy was also obliged to send annual tribute to Kumasi.

The Ashantihene (King of all Ashanti) reigns over all and chief of the division of Kumasi, the nation’s capital. He is elected in the same manner as all other chiefs. In this hierarchical structure, every chief swear fealty to the one above him—from village and subdivision to division to the chief of Kumasi, and the Ashantihene swears fealty to the State.

The elders and the people (public opinion) circumscribe the power of the Ashantihene, and the chiefs of other divisions considerably check the power of the King. This in practical effect creates a system of checks and balances. Nevertheless, as the symbol of the nation, the Ashantihene receives significant deference ritually for the context is religious in that he is a symbol of the people, living, dead or yet to be born, in the flesh. When the king commits an act not approved of by the counsel of elders or the people, he could possibly be impeached, and made into a common man.

The existence of aristocratic organizations and the council of elders is evidence of an oligarchic tendency in Ashanti political life. Though older men tend to monopolize political power, Ashanti instituted an organization of young men, the nmerante, that tend to democratize and liberalize the political process. The council of elders undertake actions only after consulting a representative of the Young Men. Their views must be taken seriously and added into the conversation.

Obirempon

Below the Asantahene, local power was invested in the obirempon of each locale. The obirempon (literally "big man") was personally selected by the Asantahene and was generally of loyal, noble lineage, frequently related to the Asantahene. Obirempons had a fair amount of legislative power in their regions, more than the local nobles of Dahomey but less than the regional governors of the Oyo Empire. In addition to handling the region's administrative and economic matters, the obirempon also acted as the Supreme Judge of the region, presiding over court cases.

Elections

The election of chiefs and the Asantehene himself followed a pattern. The senior female of the chiefly lineage nominated the eligible males. This senior female then consulted the elders, male and female, of that line. The final candidate is then selected. That nomination is then sent to a council of elders, who represent other lineages in the town or district. The Elders then present the nomination to the assembled people.

If the assembled citizens disapprove of the nominee, the process is restarted. Chosen, the new chief is en-stooled by the Elders, who admonish him with expectations. The chosen chief swears a solemn oath to the Earth Goddess and to his ancestors to fulfill his duties honorably in which he “sacrifices” himself and his life for the betterment of the Oman (State).

This elected and en-stooled chief enjoys a great majestic ceremony to this day with much spectacle and celebration. He reigns with much despotic power, including the ability to make judgments of life and death on his subjects. However, he does not enjoy absolute rule. Upon the stool, the Chief is sacred, the holy intermediary between people and ancestors. His powers theoretically are more apparent than real. His powers hinge on his attention to the advice and decisions of the Council of Elders. The chief can be impeached, de-stooled, if the Elders and the people turn against him. He can be reduced to man, subject to derision for his failure. There are numerous Ashanti sayings that reflect the attitudes of the Ashanti towards government.

"When a king has good counselors, his reign is peaceful"

"One man does not rule a nation"

"The reign of vice does not last"

Communication in Asanteman

The Ashanti also invented a talking drum. They drummed messages to the extents of over 200 miles (321.8 kilometers), as rapidly as a telegraph. Twi, the language of the Ashanti is tonal and more meaning is generated by tone than in English. The drums reproduced these tones, punctuations, and the accents of a phrase so that the cultivated ear hears the entirety of the phrase itself. The Ashanti readily hear and understood the phrases produced by these “talking drums.” Standard phrases called for meetings of the chiefs or to arms, warned of danger, and broadcast announcements of the death of important figures. Some drums were used for proverbs and ceremonial presentations.

Legal system

The Ashanti state, in effect, was a theocracy. It invokes religious rather than secular-legal postulates. What the modern state views as crimes, Ashanti view as sins. Antisocial acts disrespect the ancestors, and only secondarily harmful to the community. If the chief or King fail to punish such acts, he invokes the anger of the ancestors, and is therefore in danger of impeachment. The penalty for some crimes (sins) is death, but this is seldom imposed, rather banishment or imprisonment.

The King typically exacts or commutes all capital cases. These commuted sentences by King and chiefs sometimes occur by ransom or bribe; they are regulated in such a way that they should not be mistaken for fines, but are considered as revenue to the state, which for the most part welcomes quarrels and litigation. Commutations tend to be far more frequent than executions.

Ashanti are repulsed by murder, and suicide is considered murder. They decapitate those who commit suicide, the conventional punishment for murder. The suicide thus had contempt for the court, for only the King may kill an Ashanti.

In a murder trial, intent must be established. If the homicide is accidental, the murderer pays compensation to the lineage of the deceased. The insane cannot be executed because of the absence of responsible intent. Except for murder or cursing the King; in the case of cursing the king, drunkenness is a valid defense. Capital crimes include murder, incest within the female or male line, and intercourse with a menstruating woman, rape of a married woman, and adultery with any of the wives of a chief or the King. Assaults or insults of a chief or the court or the King also carried capital punishment.

Cursing the King, calling down powers to harm the King is considered an unspeakable act and carries the weight of death. One who invokes another to commit such an act must pay a heavy indemnity. Practitioners of sorcery and witchcraft receive death but not by decapitation, for their blood must not be shed. They receive execution by strangling, burning, or drowning.

Ordinarily, families or lineages settle disputes between individuals. Nevertheless, such disputes can be brought to trial before a chief by uttering the taboo oath of a chief or the King. In the end, the King's Court is the sentencing court, for only the King can order the death penalty. Before the Council of Elders and the King's Court, the litigants orate comprehensively. Anyone present can cross-examine the defendant or the accuser, and if the proceedings do not lead to a verdict, a special witness is called to provide additional testimony. If there is only one witness, whose oath sworn assures the truth is told. Moreover, that he favors or is hostile to either litigant is unthinkable. Cases with no witness, like sorcery or adultery are settled by ordeals, like drinking poison.

Ancestor worship establishes the Ashanti moral system, and it provides thus the principle foundation for governmental sanctions. The link between mother and child centers the entire network, which includes ancestors and fellow men as well. Its judicial system emphasizes the Ashanti conception of rectitude and good behavior, which favors harmony among the people. The rules were made by Nyame (God) and the ancestors and one must behave accordingly.

The Ashanti armies

The Ashanti armies served the empire well, supporting its long period of expansion and subsequent resistance to European colonization. Armament was primarily with firearms, but some historians hold that indigenous organization and leadership probably played a more crucial role in Ashanti successes.[15] These are, perhaps, more significant when considering that the Ashanti had numerous troops from conquered or incorporated peoples, and faced a number of revolts and rebellions from these peoples over its long history. The political genius of the symbolic "golden stool" and the fusing effect of a national army however, provided the unity needed to keep the empire viable. Total potential strength was some 80,000 to 100,000 making the Ashanti army bigger than the better known Zulu, comparable to Africa's largest- the legions of Ethiopia.[16] While actual forces deployed in the field were less than potential strength, tens of thousands of soldiers were usually available to serve the needs of the empire. Mobilization depended on small cadres of regulars, who guided and directed levees and contingents called up from provincial governors. Organization was structured around an advance guard, main body, rear guard and two right and left wing flanking elements. This provided flexibility in the forest country the Ashanti armies typically operated in. The approach to the battlefield was typically via converging columns, and tactics included ambushes and extensive maneuvers on the wings. Unique among African armies, the Ashanti deployed medical units to support their fighters. This force was to expand the entire substantially and continually for over a century, and defeated the British in several encounters.[16]

European Contact

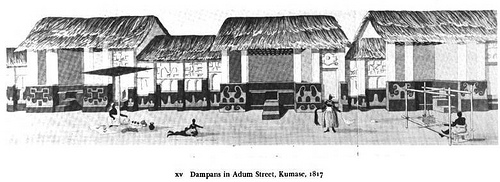

European contact with the Ivory Coast region of Africa began in the 15th century. This led to trade in ivory, slaves, and other goods which gave rise to kingdoms such as the Ashanti. On May 15, 1817 the Englishman Thomas Bowdich entered Kumasi. He remained there for several months, was impressed and on his return to England wrote a book, Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, which was disbelieved as it contradicted prevailing prejudices. Joseph Dupuis, the first British consul in Kumasi, arrived on March 23, 1820. Both Bowdich and Dupuis secured a treaty with the Asantehene. However, the governor, Hope Smith, did not meet Ashanti expectations.[17]

Wars of the Asante

From 1806 until 1896, the Asante Union was in a perpetual state of war involving expansion or defense of its domain. The Asante's exploits against other African forces made it the paramount power in the region. Its impressive performance against the British also earned it the respect of European powers. Far less known than its Zulu contemporaries, Asanteman was one of the few African states to decisively defeat the British Empire in not only a battle but a war.

Asante-Fante War

In 1806, the Ashanti pursued two rebel leaders through Fante territory to the coast. The British refusal to surrender the rebels led to an Ashanti attack. This was devastating enough that the British handed over a rebel; the other escaped.[18] In 1807 disputes with the Fante led to the Ashanti–Fante War, in which the Ashanti were victorious under Asantehene Osei Bonsu ("Osei the whale").

Ga-Fante War

In the 1811 Ga–Fante War, a coalition of Asante and Ga fought against an alliance of Fante, Akwapim and Akim states. The Asante war machine was successful early on defeating the alliance in open combat. However, Asante were unable to completely crush their enemies and were forced to withdraw from the Akwapim hills in the face of guerilla tactics. They did, however, manage to capture a British fort.

Ashanti-Akim-Akwapim War

In 1814 the Ashanti launched an invasion of the Gold Coast, largely to gain access to European traders. In the Ashanti–Akim–Akwapim War, the kingdom faced the Akim-Akwapim alliance. After several battles, some of which went in favor of the Asante and, some of which went in favor of the out numbered Akim-Akwapim alliance the war ended. Even though the outnumbered Akim-Akwapim won some key battles and had moments of glory by 1816, Asanteman was established on the coast.

Anglo-Ashanti Wars

First Anglo-Ashanti War

The first of the Anglo-Ashanti wars occurred in 1823. In these conflicts, Asanteman faced off, with varying degrees of success, against the British Empire residing on the coast. The root of the conflict traces back to 1823 when Sir Charles MacCarthy, resisting all overtures by the Ashanti to negotiate, led an invading force. The Ashanti defeated this, killed MacCarthy, took his head for a trophy and swept on to the coast. However, disease forced them back. The Ashanti were so successful in subsequent fighting that in 1826 they again moved on the coast. At first they fought very impressively in an open battle against superior numbers of British allied forces, including Denkyirans. However, the novelty of British rockets caused the Ashanti army to withdraw.[19] In 1831, a treaty led to thirty years of peace with the Pra River accepted as the border.

Second Anglo-Ashanti War

With the exception of a few Ashanti light skirmishes across the Pra in 1853 and 1854, the peace between Asanteman and the British Empire had remained unbroken for over 30 years. Then, in 1863, a large Ashanti delegation crossed the river pursuing a fugitive, Kwesi Gyana. There was fighting, casualties on both sides, but the governor's request for troops from England was declined and sickness forced the withdrawal of his West Indian troops. The war ended in 1864 as a stalemate with both sides losing more men to sickness than any other factor.

Third Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1869 a European missionary family was taken to Kumasi. They were hospitably welcomed and were used as an excuse for war in 1873. Also, Britain took control of Ashanti land claimed by the Dutch. The Ashanti invaded the new British protectorate. General Wolseley and his famous Wolseley ring were sent against the Ashanti. This was a modern war, replete with press coverage (including by the renowned reporter Henry Morton Stanley) and printed precise military and medical instructions to the troops.[20] The British government refused appeals to interfere with British armaments manufacturers who were unrestrained in selling to both sides.[21]

All Ashanti attempts at negotiations were disregarded. Wolseley led 2,500 British troops and several thousand West Indian and African troops to Kumasi. The capital was briefly occupied. The British were impressed by the size of the palace and the scope of its contents, including "rows of books in many languages." [22] The Ashanti had abandoned the capital. The British burned it.[23] The Asantahene (the king of the Ashanti) signed a harsh British treaty on July 1874 to end the war and start the gradual destruction of the Asante Union.

Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War

In 1891, the Ashanti turned down an unofficial offer to become a British protectorate. Wanting to keep French colonial forces out of Ashanti territory (and its gold), the British were anxious to conquer Asanteman once and for all. Despite being in talks with the kingdom about making it a British protectorate, Britain began the Fourth Anglo-Ashanti War in 1894 on the pretext of failure to pay the fines levied on the Asante monarch after the 1874 war. The British were victorious and Asanteman was forced to sign a treaty of protection.

Fall of Asanteman

In December 1895, Sir Francis Scott left Cape Coast with an expedition force. It arrived in Kumasi in January 1896. The Asantehene directed the Ashanti to not resist. Shortly thereafter, Governor William Maxwell arrived in Kumasi as well. Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh was deposed and arrested.

Britain annexed the territories of the Ashanti and the Fanti in 1896, and Ashanti leaders were sent into exile in the Seychelles. The Asante Union was dissolved. Robert Baden-Powell led the British in this campaign. The British formally declared the coastal regions to be the Gold Coast colony. A British Resident was permanently placed in the city, and soon after a British fort.

Ashanti Uprising of 1900

As a final measure of resistance, the remaining Asante court not exiled to the Seychelles mounted an offensive against the British Residents at the Kumasi Fort. The resistance was led by Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen-Mother of Ejisu. From March 28 to late-September 1900, the Asante and British were engaged in what would become known as the War of the Golden Stool. In the end, Asantewaa and other Asante leaders were also sent to Seychelles to join Prempeh I. In January 1902, Britain finally added Asante to its protectorates on the Gold Coast.

|

|||||

See also

- Ashanti

- Anglo-Ashanti wars

- History of Ghana

- List of rulers of Asante

- African military systems (1800–1900)

- African military systems to 1800

- African military systems after 1900

References

- ↑ Edgerton, Robert B: "Fall of the Asante Empire: The Hundred Year War for Africa's Gold Coast" Free Press, 1995

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Obeng, J. Pashington: "Asante Catholicism: Religious and Cultural Reproduction Among the Akan of Ghana", page 20. BRILL, 1996

- ↑ Ashanti.com.au - Our King

- ↑ Ashanti.com.au - Ashanti

- ↑ Ghana - The Precolonial Period

- ↑ Alan Lloyd, The Drums of Kumasi, Panther, London, 1964, pp. 21-24

- ↑ Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, St.Martin's, New York, 1995 (1989), p. 194

- ↑ Giblert, Erik Africa in World History: From Prehistory to the Present 2004

- ↑ Shillington, loc. cit.

- ↑ Asante empire

- ↑ Johann Gottlieb Christaller, Ashanti proverbs: (the primitive ethics of a savage people), 1916, pp. 119-20

- ↑ Alfred Burdon Ellis, The Tshi-speaking peoples of the Gold Coast of West Africa, 1887. p. 290

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. The Historical encyclopedia of world slavery, Volume 1, 1997. p. 53

- ↑ Shillington, op. cit. p. 195

- ↑ Bruce Vandervort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830-1914, Indiana University Press: 1998, pp. 16-37

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Vandervort, op. cit

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid. pp. 28-38

- ↑ Lloyd, op. cit. pp. 24-27

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid pp. 39-53

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid pp. 88-102

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid p. 96

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid pp. 172-174

- ↑ Lloyd, Ibid p. 175

External links

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]

- [4]

- [5]

- BBC Country Profile - Ghana

- Encyclopedia Britannica, Country Page - Ghana

- CIA World Factbook - Ghana

- Ghana at the Open Directory Project

- US State Department — Ghana includes Background Notes, Country Study and major reports

- Ghana: And Annotated List of Books and Other Resources for Teaching About Ghana

- [6] Asante Catholicism at Googlebooks]

- Ashanti Page at the Ethnographic Atlas, maintained at Centre for Social Anthropology and Computing, University of Kent, Canterbury

- Ashanti Kingdom at the Wonders of the African World, at PBS

- Ashanti Culture contains a selected list of Internet sources on the topic, especially sites that serve as comprehensive lists or gateways

- The Story of Africa: Asante — BBC World Service

- Web dossier about the Asante Kingdom: African Studies Centre, Leiden